After the Republic of Texas was annexed to the United States in late 1845, Texans had high hopes that the federal government would do what the impoverished Republic had been unable to do: subdue the aggressive Indian tribes on the new state's western frontier and open the vast emptiness of West Texas to safe Anglo settlement. Instead, the annexation of Texas soon precipitated the Mexican War, which kept the United States Army preoccupied with events south of the Rio Grande until 1849.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war in 1848 and transferred ownership of the present American Southwest and California from Mexico to the United States, also placed an obligation upon the U.S. government to protect Mexico from raids across the new international border by the Indian tribes of the North. The Comanches and Kiowas, ferocious South Plains horsemen who had wreaked havoc on Texas frontier settlements for 20 years, had from time immemorial considered northern Mexican towns and haciendas their personal raiding ground and commissary.

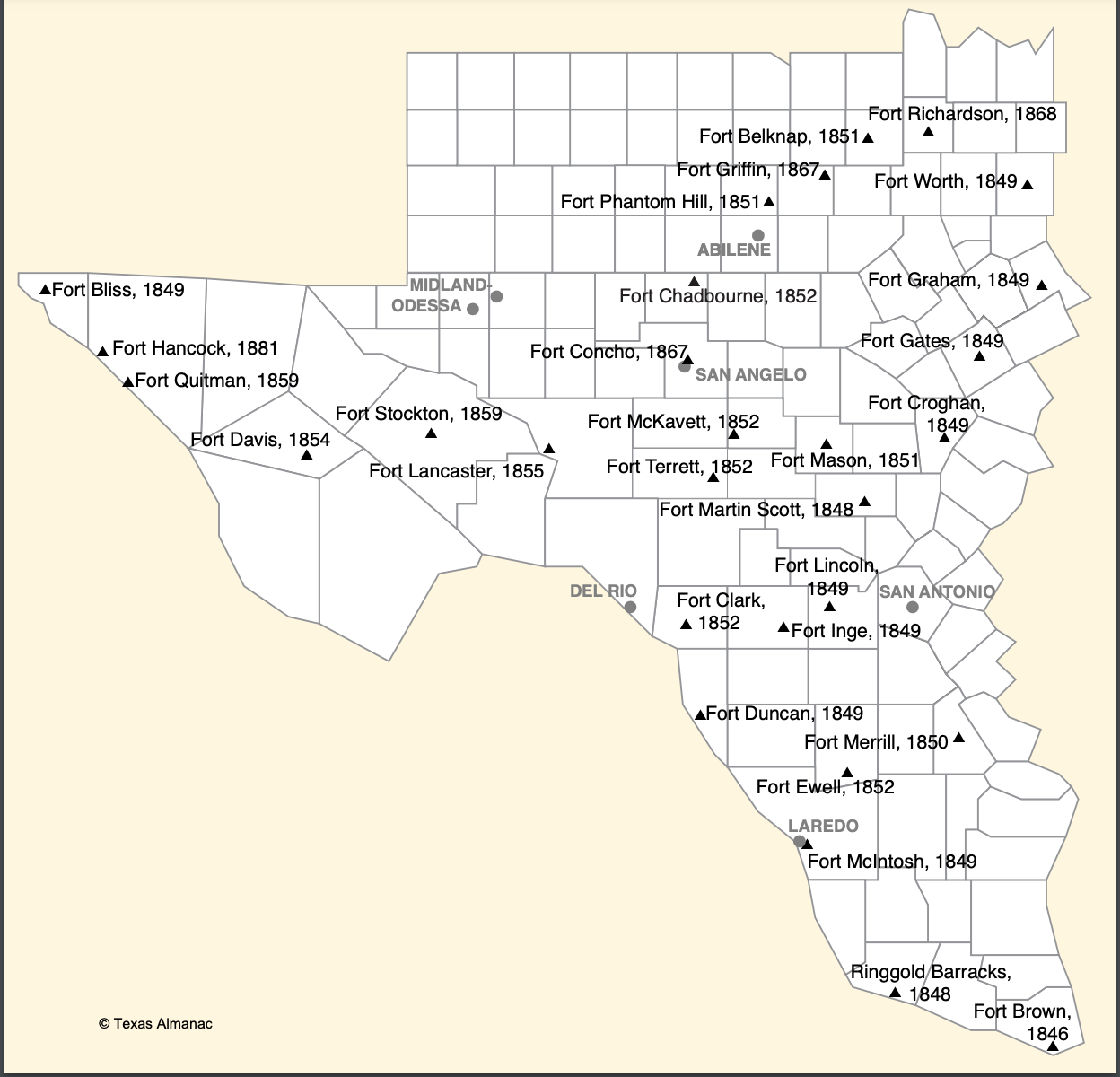

As the history of the next quarter-century would prove, this promise to Mexico was one the American government couldn't keep. Nor could it effectively protect its own settlers on the wild western edge of Texas settlement. But in October 1849, it set about trying. Brevet Maj. Gen. George M. Brooke, commanding the 8th Military Department at San Antonio, ordered the establishment of a line of forts along the Rio Grande from Brownsville to Eagle Pass, and northward from there to the Red River.

Westward Expansion

When Gen. Brooke issued his order, the California gold rush was under way. The southern route to the gold fields crossed the Texas wilderness from San Antonio to the Pass of the North (present-day El Paso) and on to the West Coast. The hopeful pilgrims traveling that cruel road across the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts had to be protected, too.

As Anglo settlement quickly pressed beyond the first forts, some of which were still under construction, the U.S. Army in 1851–52 began establishing a second line of posts about 200 miles west of the first. While the new forts were being erected, many of the older ones were abandoned or consolidated with the newer ones. For example, Fort Gates, established in October 1849 near present-day Gatesville in Coryell County, and Fort Lincoln, built in July 1849 a mile north of present-day D'Hanis in Medina County, were evacuated in 1852 because the frontier already had passed them by.

By 1853, about one-third of the U.S. Army was stationed in Texas, many of the troops serving in primitive, undermanned outposts along the border and the western frontier. Brevet Lt. Col. William Grigsby Freeman set out in June of that year on the first inspection tour of those new forts and later wrote a detailed report to the assistant adjutant general in Washington. His report paints a vivid picture of the earliest U.S. Army installations on Texas soil and the kind of life the soldiers endured in them.

A Thorough Inspection

The first post Freeman inspected was Fort Ewell, "situated on the right, or south, bank of the Nueces River at the point where it is crossed by the road leading from San Antonio to Laredo." The fort, he found, was on slightly elevated ground, but it was surrounded by a salt marsh. It lacked timber and stone for building and grazing for the animals. The soldiers had been unable even to get a kitchen garden to grow. "Indeed a less inviting spot for occupation by troops cannot well be conceived," he wrote. When he was about to depart Ewell, a rainstorm flooded the marsh around the post and held him prisoner for five days, "and even then I was compelled to swim my animals to get away."

He recommended that Fort Ewell be moved to a better spot 40 miles away, but the army soon decided to abandon it instead.

The damp colonel made a quick trip to Fort Merrill, about 60 miles northwest of Corpus Christi, then on to Fort Brown, situated just below Brownsville on the Rio Grande. The site of Fort Brown had been thought to be a healthful one, he wrote, but in the last two years "it has been visited by four epidemics – yellow fever, cholera and the dengue twice." During the last quarter of 1852 alone, 189 of the post's 459 men came down with dengue fever.

Ringgold Barracks, upriver from Brownsville, seemed in a more healthful location. It stood on a high bank of the Rio Grande within half a mile of a village of 300 souls called Rio Grande City, "a place of some notoriety in the late frontier disturbances." Freeman was pleased to find a reading room at Ringgold, "with a number of well selected books and newspapers for the use of the enlisted men — such a provision for their instruction and amusement is worthy of general introduction."

Freeman then traveled 120 miles farther upstream to Fort McIntosh, just outside Laredo, an old Mexican village of about 800 people "of which not more than 40 are Americans." Across the river, he noticed another village had sprung up since the peace with Mexico. It was called "New Laredo." Fort McIntosh had been without a medical officer for more than a month. Freeman discovered a number of sick men in the post hospital, "but no citizen physician could be obtained in the neighborhood."

The most distant of the line of Rio Grande posts, Fort Duncan, stood across a deep ravine from Eagle Pass, a village comprising "eight or 10 tolerably good buildings and the same number of mud hovels occupied by the lower order of Mexicans." There also were "three or four stores for sale of goods principally adapted to the Mexican market." The illnesses suffered by Fort Duncan's soldiers, Freeman found, were "those occasioned by intemperance and, during the winter months, by the sudden changes of temperature caused by northers."

A Fort of Primary Importance

Fort Duncan completed Freeman's inspection of the Rio Grande forts. He turned northward to inspect Fort Clark and Fort Inge on the San Antonio–El Paso road. On Aug. 1, 1853, he arrived at Fort Clark, near the present-day town of Brackettville, where troops were constructing comfortable quarters for themselves on land the government leased from Samuel A. Maverick of San Antonio.

The colonel liked what he saw: "I regard Fort Clark as a point of primary importance, being the limit of arable land in the direction of El Paso, and from its salient position looking both to the Rio Grande and Indian frontiers. It ought to have a strong garrison of horse and foot, and it is well fitted for a Cavalry station, timber for building stables being convenient, and an abundance of excellent grazing in the immediate vicinity."

Freeman had a good eye. Fort Clark would be an important post throughout the Indian wars and beyond. After the Civil War, it would be home for the intrepid Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts, or Black Seminole Scouts, descendants of slaves who had escaped into the Florida Everglades many years earlier and had been adopted into the Seminole tribe. When the government removed the Seminoles to a reservation in Oklahoma, their black tribesmen went with them. They won renown as trackers and would prove invaluable to the U.S. Army throughout West Texas during the wars against the Plains tribes and the Apaches. Four Black Seminoles won the Medal of Honor during their service at Fort Clark.

Fort Clark remained a major post until 1944, when it was deactivated. It was one of the last horse cavalry posts to go.

Freeman was less impressed with nearby Fort Inge on the Frio River. "The men," he wrote, "occupy two buildings constructed of upright poles, chinked up, with thatched roofs. These, besides being insufficient, are in a wretched state of dilapidation. Part of the troops also live in tents." The regimental band, he noted, "was very small and not mounted."

Freeman Heads North

From Inge, Freeman returned to San Antonio to refit before beginning his tour of the northern Texas posts. He began at Fort Martin Scott, a tiny post near Fredericksburg that served mainly as a forage depot for wagon trains supplying the upper posts, and then in mid-August he continued to Fort Mason, 23 miles from San Saba. "Fort Mason was the first post in Texas at which I met Indians," Freeman wrote. "They were the Tonkaway tribe, some 30 in number, and had come in to beg, and a more squalid, half-starved looking race I have never seen." He found Mason to be a well-built post manned by well-trained soldiers. By November 1853, the army had decided to abandon it, but Fort Mason did not finally close until 1869.

At Fort McKavett, two miles from the source of the San Saba River, he discovered himself finally in real Indian country. Three Comanche bands led by Yellow Wolf, Ketunseh and San-a-co were living on the Concho River and at the headwaters of the Colorado, within 60 to 100 miles of the post.

The men at McKavett were "variously armed and clothed, which besides the inconvenience attending its instruction, greatly detracts from its appearance on parade occasions." The post was "wretchedly equipped, being deficient in many essential articles and without the means of keeping in order those on hand." It had only 30 serviceable horses. The nearest post office was at San Antonio, 164 miles away.

"During the whole summer," Freeman wrote, "the men were engaged in building the post; they were exposed during the day to the heat of the sun, and at night they slept either upon the ground or in tents, and alcoholic liquors were used in excess."

Fort Terrett, on the North Fork of the Llano River, was under construction, too. The fort's barracks were "mere shelters" without doors, floors or windows. The best thing Freeman found at Fort Terrett was the band, which "though small, is quite good, and does much to relieve the monotony of garrison life at an isolated, frontier station."

Rustic Conditions

Freeman returned to Fort McKavett, then departed for Fort Chadbourne, 95 miles to the northwest on Oak Creek, a small tributary of the Colorado. It was a four-day journey. Except for the officers, who lived in "two or three rude, jacal huts," the troops there were still living in tents.

"The Comanches are the only Indians who have visited the post since its establishment," he wrote. "I could obtain only a vague estimate of their numbers. They have no permanent camps, but for the last year the band of San-a-co, one of the principal chiefs, has lived within 50 or 60 miles of the post."

At Fort Phantom Hill, between the Elm and Clear Forks of the Brazos River near present-day Abilene, the soldier's life was no better than at McKavett. "The aspect of the place is uninviting," Freeman wrote. "No post visited, except Fort Ewell, presented so few attractions."

He couldn't even review the troops because nearly all of them were raw, untrained recruits who hadn't yet learned how to march, and 50 of them didn't yet even have weapons. To complete the dismal scene: "The officers and soldiers are living in pole huts built in the early part of last year. They are now in a dilapidated condition. The company quarters will, in all probability, fall down during the prevalence of the severe northers of the coming winter."

At Fort Belknap, on the Clear Fork of the Brazos northeast of Phantom Hill, the prospect was brighter. There was plenty of good stone and brick clay for construction; the post stood over a field of bituminous coal that could be dug for fuel, and excellent springs were only a few hundred yards away.

The post had been visited recently by small bands of Caddos, Anadarkos, Ionies, Wacos, Keechies and Tawakonis, as well as 300 Comanches under the ubiquitous Buffalo Hump and San-a-co. "Their camps are moveable," Freeman wrote, "but during the winter they live within 40 miles, on the Clear Fork."

From Belknap, Freeman swung eastward to a small collection of log buildings called Fort Worth, at the mouth of the Clear Fork of the Trinity River. "The nearest towns or villages are Dallas, with 350 inhabitants, 38 miles east, and Birdville and Alton, with a population of 50 each, distant 9 and 35 miles respectively."

Fort Worth had been established in 1849. When Freeman arrived there in September 1853, its commander had gotten orders to abandon the post and move his troops to Fort Belknap.

"I was gratified to find – it was the solitary exception throughout my tour – the Guard House, that saddest of all places in a garrison, without a single prisoner. Bvt. Maj. Merrill informs me that most of his men belong to the temperance society, and that he has rarely occasion to confine any one of them."

The last two forts on Freeman's tour – Fort Graham, 56 miles southwest of Fort Worth, and Fort Croghan, in the center of Texas 50 miles northwest of Austin – also were in the process of shutting down. With a few exceptions, most of the other posts he visited would follow them into oblivion within a few years. Settlers already were pushing the frontier miles beyond their usefulness.

They hadn't been a deterrent against Indians raids anyway. They never had enough troops or the right equipment to perform their mission. Most of their troops were infantry. To expect them to chase down on foot the greatest horsemen in the world was sheer governmental folly. The Comanches and Kiowas who visited the forts and took a look around must have had a good laugh when they returned to their camps.

Why did the army keep its mounted troops at its eastern forts, far from the frontier, while sending its infantry to the western posts, where the Indian horsemen roamed? Brevet Gen. Persifor Smith, commander of the Department of Texas, had decided to quarter his horses where the forage was best. And there was more grass in the east.

The Trans-Pecos Posts

In late 1848, the War Department also had authorized the establishment of a post at the western tip of Texas, across the Rio Grande from the Mexican village of El Paso del Norte (present-day Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua). Its mission would be to defend the border and protect California-bound travelers and the few local settlers from Indian attack. Brevet Maj. Jefferson Van Horne and 257 soldiers arrived there in September 1849. The troops occupied several sites along the river, but in 1851 they were ordered to withdraw to Fort Fillmore, 40 miles to the north in New Mexico. In January 1854 the border post was re-established and named Fort Bliss.

Later that year, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis ordered the establishment of a second post in the Trans-Pecos to defend the San Antonio–El Paso road. The road intersected several war trails traveled by the Comanches and Apaches on their raids into and out of Mexico.

In October 1854, Gen. Smith personally selected – for its "pure water and salubrious climate" – the site of Fort Davis (named for the secretary of war) near Limpia Creek at the southern base of the Davis Mountains (also named for the secretary). Six companies of infantry under Lt. Col. Washington Seawell constructed a primitive post of mud and wood in a box canyon near the creek.

In August 1855, Capt. Stephen Carpenter and two infantry companies established Fort Lancaster on Live Oak Creek above its confluence with the Pecos River near the present-day town of Sheffield. In September 1858, Capt. Arthur T. Lee and his infantry command established Fort Quitman on a barren plain of the Rio Grande, 80 miles downstream from Fort Bliss. And in March 1859 Fort Stockton was established at Comanche Springs, a favorite watering spot on that tribe's war trail into Mexico.

The duties of the soldiers at all these posts were to escort freight wagon trains and the mail, patrol their segments of the road to keep track of the Indians' whereabouts, and pursue and punish the raiders – still an impractical, if not impossible, mission for infantry in such harsh country against such skillful horsemen.

The Civil War Years

Before the soldiers at the Trans-Pecos forts could build permanent, comfortable quarters for themselves and their animals, Texas seceded from the Union in 1861 and joined the Confederacy. Brig. Gen. David E. Twiggs, commander of the 8th U.S. Military District, ordered the federal garrisons to evacuate all the posts and surrender them to Confederate authorities. Elements of the 2nd Regiment of the Texas Mounted Rifles occupied most of the West Texas forts, some for a few months, some for a year or more.

During the year that Col. John R. Baylor and Confederate troops manned Fort Davis, a detachment of cavalry gave chase to an Apache raiding party. Thinking he had overtaken the raiders somewhere in the Big Bend, Lt. Reuben Mays and his 13 men rode into an ambush. The Apaches wiped out the soldiers, and only a Mexican guide escaped.

In 1862, the soldiers from the Trans-Pecos posts marched on to Fort Bliss and were part of the army led by Brig. Gen. Henry Hopkins Sibley that attempted to conquer New Mexico for the Confederacy. After the disastrous Battle of Glorieta Pass, the Confederates abandoned the Trans-Pecos and retreated to San Antonio. The deserted forts fell into ruin. Apaches looted and burned much of Fort Davis.

Except for Fort Bliss, which Union troops reoccupied after Glorieta, the war left the frontier settlements and travelers as naked to Indian attack as they had been before Texas joined the Union. Many families abandoned their homes and pulled back to more populous areas. Others "forted up" together and depended on a few companies of Texas Rangers and minuteman volunteers to protect them.

U.S. Army Returns to Texas

When the Civil War ended, the U.S. Army returned to Texas, this time to stay until the frontier was tamed. In 1867 and 1868, federal troops reoccupied Fort Davis, Fort Stockton, Fort Lancaster and Fort Quitman, this time building permanent housing and facilities of stone and adobe to replace the uncomfortable and unsanitary pre-war jacales.

In addition, the army built a trio of new forts to contend with the Comanche threat east of the Pecos. On "a flat, treeless, dreary prairie" beside the Concho River at present-day San Angelo, it established Fort Concho to replace old Fort Chadbourne. On the Clear Fork of the Brazos River near present-day Albany, it established Fort Griffin, and the older posts of Belknap, Phantom Hill and Chadbourne were reduced in status to subposts of Griffin. On Lost Creek, a tributary of the Trinity near Jacksboro, it built Fort Richardson, the northernmost army post in Texas. Much later, Camp Rice, later to be renamed Fort Hancock, was built on the Rio Grande downstream from El Paso as a subpost of Fort Davis to defend against Indians and Mexican bandits.

From these posts and a few of the older ones such as Fort Clark, the army over the next 15 years or so would eventually eliminate the Indian resistance to Anglo settlement of West Texas. The names of some of the officers who commanded the forts would be writ large in the broader history of the American West. And events that happened at some of the forts would become important chapters in the history of the army and in frontier folklore.

The West Texas Wars

In early 1871, Col. Ranald Slidell Mackenzie, who at various times commanded Fort Brown, Fort McKavett, Fort Clark, Fort Concho and Fort Richardson, began a series of expeditions from Concho into the Panhandle and the Llano Estacado in pursuit of renegade Comanches, Kiowas and other Indians who continued to cross the Red River and raid into Texas from their reservations near Fort Sill, Indian Territory. Two years later, operating from Fort Clark with cavalry and Black Seminole trackers, Mackenzie made an illegal raid into Mexico in pursuit of Indian cattle thieves. He burned a Kickapoo village in Coahuila and brought 40 Kickapoo captured women and children back to Texas. His victory brought a period of peace to the border but cattle raids resumed in the late 1870s.

In July 1874, Mackenzie's was one of five army commands ordered to close in on Indian hideouts in the canyons along the eastern edge of the Llano Estacado. The troops engaged the Indians in several battles and skirmishes, and in November 1874, Mackenzie's command destroyed five Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne and Arapaho villages in Palo Duro Canyon and captured 1,500 horses. Mackenzie ordered the horses slaughtered, thus destroying both the buffalo-centered economy of the Southern Plains tribes and their ability to continue raiding. This conflict, which became known as the Red River War, ended on June 2, 1875, when Comanche Chief Quanah Parker arrived at Fort Sill with 407 followers and finally accepted reservation life.

During the five years after Mackenzie's victory, white hunters converged upon the Plains and systematically slaughtered the great southern buffalo herd for the animals' hides and for sport. Fort Griffin and the nearby raucous village called "The Flat" became the center of the odoriferous hide commerce and attracted hordes of gamblers, prostitutes, gunmen and thieves bent on relieving the hunters of their money. By 1881, both the Comanche presence and the buffalo were gone, so the army closed Fort Griffin.

The Victorio Campaign

But in the Trans-Pecos the army was still fighting, mostly against Apaches who were raiding across the Rio Grande from strongholds in the mountains of Chihuahua and Coahuila. In September 1879, a large band of Mescalero and Warm Springs Apaches, under the leadership of Victorio, began a series of attacks in the mountain-and-desert country west of Fort Davis. Col. Benjamin H. Grierson, a Union hero during the Civil War, led troops from forts Davis, Concho and Stockton in a campaign against the raiders. Instead of chasing the Apaches across the rugged landscape, Grierson stationed his troops around the region's few watering places and deprived the warriors of the one commodity without which even Apaches couldn't survive. After several hard-fought battles, Victorio crossed back into Mexico. Mexican troops killed him and many of his followers in the Battle of Tres Castillos in October 1880.

The Victorio campaign was the last major conflict between Indians and the U.S. Army on Texas soil.

Much of the fighting in both the Panhandle and the Trans-Pecos wars was done by black troops to whom the Plains tribes had affixed the nickname "Buffalo Soldiers" because of their curly hair. Since former slaves had served in the Union Army with distinction, Congress authorized the establishment of six regiments of black troops to serve on the post–Civil War frontier: the 9th and 10th Cavalry and the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st Infantry. In 1869, the four infantry regiments were consolidated into the 24th and 25th Infantry.

Prejudice on the Frontier

Not even the black soldier's valor could win them respect from many of the white citizens whose lives they protected. A number of white officers, including George Armstrong Custer, refused to serve as their commanders. But other white officers, Grierson most notable among them, treated the black soldiers well and achieved victory and honor in their company. They proved to be brave, reliable soldiers. Fourteen enlisted men from the black regiments and four Seminole-Negro Indian Scouts earned the Medal of Honor during the Indian wars.

The most notorious case of racial prejudice in the frontier army was the ordeal of 2nd Lt. Henry Ossian Flipper, the first black graduate of West Point, who was dismissed from the service in June 1882 after he was found guilty of "conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman" in a court-martial trial at Fort Davis.

Flipper was born into slavery in Georgia in 1856, graduated from the Military Academy in 1877 and was assigned to the 10th Cavalry. He served at forts Sill, Elliott, Concho and Quitman before coming to Fort Davis. He distinguished himself as an engineer, helped move Quanah Parker's Comanches from Palo Duro to Fort Sill, and fought in two battles during the Victorio campaign.

When Col. William Rufus "Pecos Bill" Shafter became commanding officer of Fort Davis in 1881, Flipper was both post quartermaster and in charge of the commissary. Shafter immediately relieved him of his quartermaster duties, giving that job to the regiment's quartermaster, and later filed embezzlement charges against Flipper when commissary funds were missing. The lieutenant claimed that the charges against him were motivated by race. A divided court-martial acquitted him of embezzlement but ruled him guilty of "conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman." Although dismissal was the army's punishment for such a conviction, many soldiers got lighter sentences. In Flipper's case, however, he was dismissed from the U.S. Army while with his company at Fort Quitman.

Flipper moved on to a long and distinguished career as a mining engineer in the Southwest and Mexico and even became an assistant to the U.S. secretary of the interior. He maintained his innocence of the Fort Davis charges and tried unsuccessfully on several occasions to clear his name. Almost a century after his discharge, the army "corrected" Flipper's records to show that he was "separated" from the army by "honorable" discharge, and on Feb. 19, 1999, President Bill Clinton posthumously pardoned him.

The End of an Era

With the migration of Anglo farmers, ranchers and other settlers westward behind the army, the frontier era was rushing toward its close. Fort Lancaster was abandoned in 1873 and Fort Richardson in 1878. After the removal of the South Plains tribes and the Apaches from Texas, the remaining West Texas forts settled into quiet garrison routine. Eventually, one by one, the army shut them down: Fort Quitman in 1882, Fort Stockton in 1886, Fort Concho in 1889, Fort Davis in 1891, Fort Hancock in 1895. Fort Duncan on the Rio Grande lasted until 1922. Four other border posts survived into the World War II era: Ringgold and Brown until 1944, and Clark and McIntosh until 1946. Today only Fort Bliss remains as an important 21st-century missile base.

Some of the old posts have won new life in recent years as historical treasures. Fort Davis, the largest and best preserved of them, is now a national historical site; Fort Concho is a national historical landmark; Fort Griffin, Fort Richardson, Fort McKavett and Fort Lancaster are state historical parks, and others like Fort Stockton, Fort Phantom Hill and Fort Chadbourne are cared for by local government and historical groups.

— written by Bryan Woolley for the Texas Almanac 2004–2005. Mr. Woolley was a novelist and was a senior writer for The Dallas Morning News.