By Al McGraw

The old Spanish road called the Camino Real has had many names since it first entered Texas in the late 17th century. But whatever it was called — Camino Real de los Tejas, Camino Pita, Camino Arriba, Camino de en Medio, King’s Highway, Old San Antonio Road — it was not an ordinary camino (road). Though often little more than a mule track, it was a camino real — a royal road with special status.

Our knowledge of the Camino Real is incomplete. Our understanding of the trail’s origins and its changes grow as new information is gathered and old information is reassessed. This article presents a brief overview of what is known about the road: its origins, its uses, the people who touched it and the settlements it affected.

Before detailing the routes of the royal roads in Texas, we will explore the political and practical reasons to establish caminos reales and will present the roads in their environmental and historical contexts.

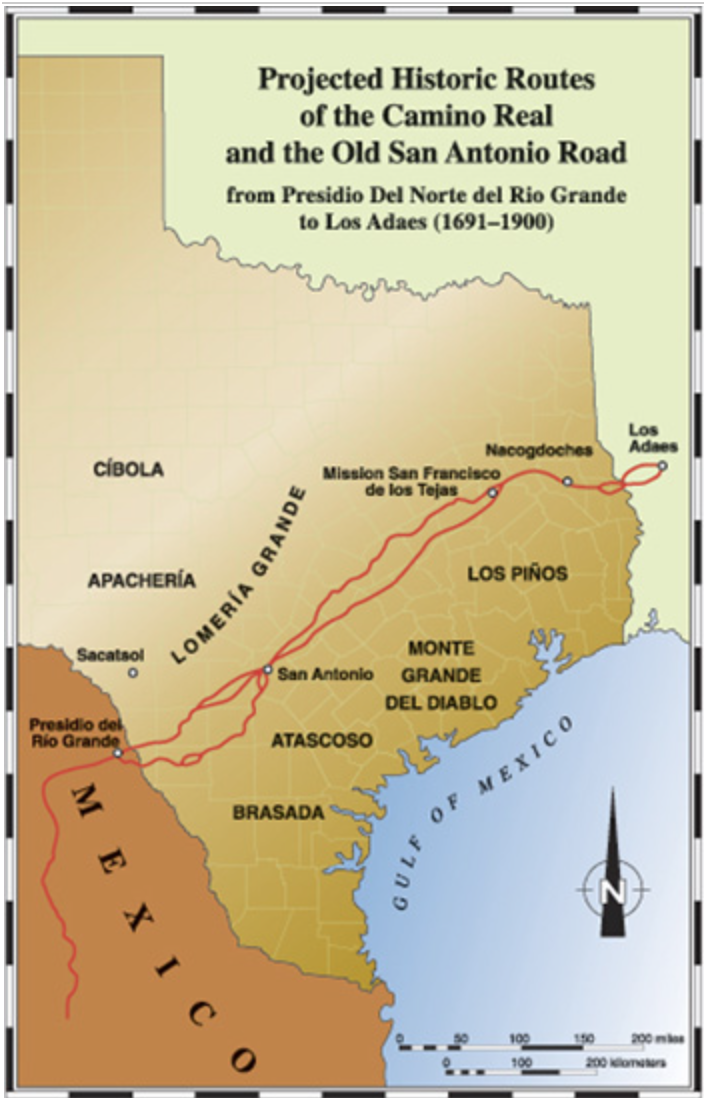

The Camino Real discussed here was a network of Spanish roads that crossed the Rio Grande into Texas from Mexico near San Juan Bautista mission and presidio at today’s Guerrero, Coahuila, Mexico — about 35 miles downstream from present-day Eagle Pass. The routes extended through San Antonio de Valero to the presidio at Los Adaes in Louisiana.

The route was developed to confront and counter French intrusion into the northeastern frontier of the Spanish borderlands. It also became the first route of evangelization by Spanish missionaries attempting to Christianize Indian groups from the Rio Grande to the Red River. Several decades later, its path from the Brazos to the Trinity rivers helped defuse the threat of Indian nations armed by and loosely allied to the French and transformed those groups into an uneasy buffer between divergent cultures. Settlements established along the component roads were among the state’s earliest cities and communities. And, in the 19th century, the trail became an important route of immigration into the republic, and later the state of Texas.

Perhaps not surprisingly, sections of the route have been incorporated into or closely parallel our modern system of highways. The Camino Real is not a dusty anachronism; it is a dynamic part of present-day culture.

Not every route used by the Spanish during their exploration and settlement of New Spain met the requirements for designation as a camino real. Caminos reales were routes that connected economically important Spanish towns, capitals of provinces and mines that possessed charters conferring royal privileges. The status granted to these villas, capitals and mining areas was extended to the routes used by government officials, military troops and others traveling between them on the business of the crown.

Origins of the Caminos Reales in New Spain

The earliest network of caminos reales, which connected the governmental center of New Spain, in what we now call Mexico City, with Spanish outposts in New Spain and in today’s United States, was based on old trade routes used by Aztecs and other Indian groups. The main long-distance trail led north from the Central Valley of Mexico between the Sierra Madre Occidental and the Sierra Madre Oriental, the principal mountain ranges that run north and south through central Mexico. The trail led to settlements such as Paquimé, a small city (now called Casas Grandes) that existed until about 1300 in today’s Mexican state of Chihuahua, 150 miles southwest of El Paso.

After Hernán Cortés conquered Mexico for Spain in 1521, the quest for precious metals sent the Spanish north on the old Indian trail. In the 1540s, silver was discovered in Querétaro, Guanajuato, San Luis Potosí and Zacatecas. As the Spanish continued moving north in search of ever-richer mines, the silver hunters and the mines required the protection of soldiers, as did the communities that developed around the mines. Missionaries also followed the ancient trail in search of souls to win.

The Spanish, led by Juan de Oñate, crossed the Rio Grande in 1598, moving through the El Paso area into what became New Mexico. In 1610, provincial governor Pedro de Peralta established Santa Fe as the capital. To connect Mexico City with the provincial capital, the Camino Real was extended from Zacatecas north through Durango, Allende, El Parral, Chihuahua and Juárez to El Paso, Albuquerque and Santa Fe.

The Camino Real Through Texas

In time, a branch of the Camino Real was established, extending northeastward from Zacatecas, passing through Saltillo and Monclova, crossing the Rio Grande near today’s Guerrero, Coahuila, and going on to San Antonio, Nacogdoches and Los Adaes. The Spanish established this branch of the road to connect the missions, presidios and other provincial governmental centers to each other and to Mexico City.

Texas’ Camino Real, sometimes known in the 18th century as the Camino Real de Los Tejas, was not a single trail. It was a network of regional routes separately known as the Camino Pita, the Upper Presidio Road; the Lower Presidio Road, also called the Camino de en Medio; the Camino Arriba; and the San Antonio-Nacogdoches Road or Old San Antonio Road of the mid-19th century, portions of which are still marked with the designation “OSR” on Texas highway maps and road signs. Throughout its three-hundred-year history, the alignments of different regional segments shifted laterally within a narrow corridor of time and space to allow travelers to avoid obstacles such as flooded rivers or hostile Indians. Most of the landmarks and destinations of the segments, however, remained constant.

Parts of these roads were not only used for travel, they also formed some of the earliest political boundaries. Near San Antonio for example, the Lower Presidio Road once separated thousands of acres of ranch land claimed by the missions of Espada and San José. The ruts of the trail are still visible in the area. In the 19th century, the Camino Real formed the boundary of many empresario grants throughout Texas. Later, it became the county line of many of the state’s first subdivisions.

Although many different trails in Texas and elsewhere were established as caminos reales, this article for simplicity will refer to the narrow corridor of contiguous regional segments from modern Guerrero across Texas as “the Camino Real.”

Indian Trails Were Basis of the Camino Real

As was true of the earlier Camino Real that extended from Mexico City to Santa Fe, large portions of the early routes across Texas were based on Indian trails of apparent antiquity that suggest a complex network of aboriginal movement, interaction and trade. The regional trails that comprised the Camino Real included portions of Caddoan, Coahuilteco, Jumano and possibly Sanan routes of travel.

Modern highways often follow these early trails. Although widely scattered across the Texas landscape, both historical Indian trails as well as prehistoric archaeological sites occasionally have been found along Spanish colonial trails and under modern highways. The precise destinations of these trails are not clear, but they certainly led to areas once known as Cíbola, Apachería, Comanchería, la Pita and Tejas.

Most historians believe the Camino Real through Texas was developed in 1691 to link the Spanish colonial missions in East Texas with the administrative center of New Spain. And those missions were established to counter the threat of French intrusion into the northern borderlands of New Spain.

The French presence in Texas, briefly established in 1685 by René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, culminated with the establishment of what has become known as Fort St. Louis on present-day Garcitas Creek in Victoria County.

La Salle’s settlement suffered miserably. Fewer than 30 people survived to the end of 1688, or perhaps into early 1689, at which time, they, with a few exceptions, were massacred by Karankawa Indians.

La Salle was not present at the disastrous end of his colony. He had been murdered March 19, 1687, by his own men far from the settlement while searching for an overland route to the Mississippi River. The vicinity of his murder included an old Indian trail, which subsequently led the expedition’s survivors to the Mississippi.

The location of La Salle’s murder and the route of the trail have not been positively identified. One possible location is noted on a composite map of early Texas dated 1773 that is housed in the Spanish military archives in Seville, Spain. A figure on the map shows a small cross and notes that La Salle died there in 1687. The location appears to be near present-day Keechi Creek west of the Trinity River. A faint line runs eastward toward Los Adaes and Louisiana; in 1773 this was a portion of the Camino Real.

After La Salle’s death, the members of his expedition continued eastward and temporarily stopped at a Caddoan Indian village near the Neches River. A confrontation among the members resulted in the death of two Frenchmen, who were buried by the villagers.

The French incursion into Spanish territory alarmed Spanish officials into authorizing a series of military entradas (expeditions) northward across the Rio Grande. The first successful Spanish expedition, that of Alonso de León in 1689, found only the scattered remnants of the destroyed settlement.

Returning in 1690 to obliterate the ruins of the French settlement, León and Franciscan priest Damián Massanet stopped at the Caddo village the French expedition had visited and were shown the Frenchmen’s graves. Subsequently, the site became the location of the short-lived San Francisco de Los Tejas. Although the mission was only briefly occupied, the nearby crossing of the Neches River remained in use through the 19th century.

Subsequent Spanish entradas served also to lengthen the Camino Real. The expedition of provincial governor Domingo Terán de los Ríos in 1691, for the purposes of exploration and establishment of missions, extended the route to East Texas.

French explorer and trader Luis Juchereau de St. Denis journeyed from Louisiana across Texas to Mexico in 1714. This expedition and St. Denis’ later travels of 1716 and 1717 formed a brief but important link in the establishment of the Camino Real. These trips also helped set the stage for Spanish, French and Indian interactions for much of the following 18th century.

St. Denis was the most influential of the early French traders in the northeastern Spanish borderlands, not only because of his command of Fort Jean Baptiste in Natchitoches and his influence with East Texas Indians, but also because of his close ties with Spanish officials in Coahuila. Domingo Ramón, son of the commandant at Coahuila, led an expedition to Louisiana in 1716, accompanied by St. Denis.

On that trip Ramón reaffirmed the Spanish presence in East Texas by establishing several missions, including the former San Francisco de los Tejas at a new location and a new mission at Los Adaes. The journal of the Ramón expedition of 1716 also identified a series of parajes, or campsites, that became associated with a subsequent early route of the Camino Real at the beginning of the 18th century.

Landmarks along the routes of St. Denis’ journeys appear to include the 1690 site of the Mission San Francisco de los Tejas and the Trinity, San Marcos, Guadalupe and San Antonio rivers. Apparently, the route of the 1717 journey was similar to the trail blazed by the Ramón expedition the previous year. A large portion of Ramón’s trail, if not all, acted as the foundation for the primary 18th-century Spanish road between Los Adaes and the Rio Grande known as the Camino de los Tejas.

The trail’s development was strengthened by the establishment of a Spanish military outpost at Los Adaes by the expedition of 1721-22, led by the Marqués de San Miguel de Aguayo.

The Routes of Texas’ Camino Real

South Texas: From the Rio Grande to San Antonio

In South Texas, the Camino Real consisted of several regional routes that crossed the Rio Grande at San Juan Bautista del Río Grande mission and presidio near the modern town of Guerrero, Coahuila. The principal routes between the Rio Grande and San Antonio were known as the Camino Pita; Upper Presidio Road; and the Lower Presidio Road, also called the Camino de en Medio, or middle road, because it was the middle of three roads leading south from San Antonio in the 18th century (the lowest route was the Laredo Road). During different decades, travelers often had a preference for a particular route, although some trails were contemporaneous and the times of their uses overlapped.

Early crossings on the Rio Grande, which included Paquache and Paso de Francia near San Juan Bautista, led into today’s southern Maverick County. Other crossings were known as Paso de las Islas, Paso de Nogal, and Paso de Diego Ramón. The trail then headed eastward toward the paraje of El Cuervo, a campsite noted by León in 1689 to be three to four leagues (approximately 2.6 miles) from the Rio Grande. The road then traveled past a series of intermittent drainages noted for their poor quality of water. In later years, the Upper Presidio Road then crossed the Frio River in the immediate vicinity of Old Frio Town in northwestern Frio County.

From the Rio Grande northeastward, the routes of the Camino Real crossed or bordered a number of distinctive natural areas. The trails led through the rocky, eroded hills that bordered the river valley. The area from the Rio Grande to just south of the Nueces River was once known as the Sabana (or savannah) Grande. The savannah was a major landmark along the Camino Real, and it was mentioned in several descriptions of the Lower Presidio Road. The routes led toward the Nueces River, avoided a large sheet of waterless inland sand dunes to the southeast known as La Costa. This area today, called the South Texas sand sheet, occupies most of Brooks County and parts of Kleberg, Jim Hogg, Kenedy, Hidalgo and Willacy counties in extreme South Texas.

The route also led across a wide expanse of thornbrush later called the Brasada. The Spanish word brasada refers to something burned or burning, such as embers or hot coals. It was commonly used in the 19th century to refer to the dense South Texas thornscrub, perhaps because of the burning heat of the ground in that area in summer, noted in several early travelers’ journals. The Brasada was roughly bounded on the north by the Lomería Grande and on the east by the Texas coastal prairies. Toward the northeast, it bordered the deep sands and forest of El Atascoso and the Tapado, the umbrella-like growth of oaks and vegetation near the Atascosa River.

The Brasada of South Texas was generally synonymous with the Llanos de las Mesteñas, the plains of vast herds of wild horses and cattle that proliferated in the region until the mid-19th century. By the 1880s there were frequent accounts of wild horses blanketing the prairies, stampeding mounts and pack mules and interfering with cattle roundups. The subsequent increase in ranching gradually destroyed all traces of these vast herds.

Early travelers in the region were concerned with the locations of water sources. Southern Texas was characterized by only a few large rivers and a number of intermittent streams and charcos, or waterholes, often described as mala agua (bad water). Names of campsites and streams such as agua verde (green water), arroyo seco (dry creek) and las lagunillas de mala agua (ponds of bad water) reflected an early distaste for certain locales. Nevertheless, these locations attracted both native Indian groups and thirsty explorers.

To the north of the trails and in the Edwards Plateau lay Apachería or Lomería Grande (large hills), home of the warlike Apaches. Later, in the 19th century, it became known as Comanchería as the invading Comanche displaced the earlier Lipan Apache. In the 17th century, the plateau was known by the Jumanos as Cíbola.

About six leagues (15.6 miles) north of the Frio River, the Upper Presidio Road forded Hondo Creek within a few hundred yards of modern Farm-to-Market Road 2200 in southwestern Medina County. Another parallel route, the Camino Pita, crossed Francisco Pérez and Chacon creeks in the vicinity of present-day Devine, just west of and parallel to Interstate 35. Projections of the route from an 1866 Medina County map show that the route crossed the Medina River just south of San Antonio near present-day Macdona in southwest Bexar County.

By the middle 1700s a new, more southerly route, the Lower Presidio Road, developed from San Antonio to the Rio Grande. Apparently the earlier upper route, Camino Pita, was still in use; it acted as the southern boundary of Rancho San Lucas, an outlying ranch of Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo in San Antonio. Farther southeastward, the Lower Presidio Road acted as the boundary between the outlying lands of missions San José and Espada.

By the early 1800s, a variant of the Upper Presidio Road was established by Governor Antonio Cordero, probably in anticipation of a soon-to-come filibuster invasion from Louisiana. Afterward, apparently, the two parallel upper routes, the Upper Presidio Road and the Camino Pita, were used contemporaneously but had different river and creek crossings.

Approaches to San Antonio

South of San Antonio, the Upper Presidio Road had several crossings of the Medina River, but the two most used were in the vicinity of modern La Coste and Castroville. The remnant fords of several significant early trails are located on a 10-mile stretch of the Medina River south of San Antonio and they include the crossings of the Camino Pita, the Camino de los Tejas, the Upper Presidio Road, the Lower Presidio Road, the San Antonio-Laredo Road and several other lesser routes.

Originally known as Penapay (also spelled Panapay) in the Indian language of Coahuilteco as recorded by Fray Massanet in 1691, the Medina River was first named a day after Easter, on April 11, 1689, by Alonso de León. An entry in León’s diary suggests that he named the river for Pedro de Medina, a 16th-century Italian astronomer whose navigational tables were used by León and his contemporaries.

Santa Anna and his army used the Medina River crossing of the Upper Presidio Road near the modern community of La Coste on their march to the Alamo in 1836.

Throughout the historical periods, all the routes of the Old San Antonio Road, from east or south, converged in the town of San Antonio near the headwaters of the San Antonio River and the now-dry San Pedro Springs. The locale, originally a large Payaya Indian encampment known as Yanaguana, was first described by Fray Massanet on June 13, 1691. The presence of the springs and the ease with which nearby fields could be irrigated were deciding factors in the location and founding of San Antonio in 1718.

The major springs of the Balcones Escarpment, such as those in San Antonio and present-day New Braunfels, attracted not only European explorers along the Camino Real, but Indian travelers as well. In 1691, Fray Massanet estimated that 3,000 Jumano Indians and associated groups were camped at Comal Springs at present-day New Braunfels.

From San Antonio de Béjar presidio, the route traveled eastward toward the Mission San Antonio de Valero (the Alamo) along the street now known as Bonham and then along Nacogdoches Road. The road crossed Cibolo Creek near the modern town of Bracken in Comal County. From there the path paralleled the Balcones Escarpment and crossed the Comal and Guadalupe rivers near Landa Park in New Braunfels.

Across the Blackland Prairie

The historical routes of the Camino Real northward from San Antonio followed two separate trails that traversed south-central Texas and converged in East Texas at several crossings of the Trinity River. The upper, probably earlier, trail crossed near the springs of the San Marcos River and turned northeastward across the Blackland Prairie toward the confluence of the Little and Brazos rivers. Along its way, it crossed the Colorado and Brushy Creek east of modern Austin and, farther along, the San Gabriel River, formerly known as the Río San Xavier. For much of the 18th century, the area between the San Gabriel and Trinity rivers was the home of thousands of Indians commonly allied against the Apache.

Sometimes consisting of as many as 21 different groups, including apostate bands fleeing from northeastern Mexico, the disparate groups, collectively known as Ranchería Grande, exploited bison commonly found on the prairies. The strategic location of the Indian groups and their sometimes open hostility toward Spaniards acted as an obstacle to travel for decades. Many of these groups temporarily coalesced into missions established for them along the San Gabriel River in the mid-1700s, but they gradually moved northeastward before disappearing from the historical record by the end of the century.

By the early 19th century, a lower route developed across south-central Texas that paralleled the earlier, upper route. Confusingly known as the “upper” road, the Camino Arriba was commonly shown on maps drawn by Stephen F. Austin in the 1820s.

A large portion of the trail crossed dense woodlands called the Monte Grande (del Diablo) southeast of the Blackland Prairie. For the most part, the modern Old San Antonio Road (OSR) and State Highway 21 follow this route of the Camino Real to East Texas. Below the confluence of the Blanco and San Marcos rivers near present-day San Marcos, a portion of the old road and its river crossing were identified in 1991. Several years later at the crossing, archaeologists located the remains of the first townsite of San Marcos, San Marcos de Neve, established near the end of the Spanish Colonial period.

In large part, the Camino Arriba became known as the Old San Antonio (-Nac-ogdoches) Road in the middle 19th century. This route was surveyed by V.N. Zivley, a professional engineer, in 1915, and commemorated through the efforts of Claudia Norvall and the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) by the placement of granite markers along the route. These actions contributed significantly to the recognition of the King’s Highway or the Old San Antonio Road (OSR).

Eastward Toward Tall Texas Pines

The varying routes of the Camino Real corridor in south and central Texas historically consisted of four distinct trails often associated with the woodland region’s distinctive system of small prairies. Landmarks along the Camino de los Tejas, the Camino Arriba and the Old San Antonio Road reflect the rich, diverse cultural heritage of the region, which includes Native American and Spanish Colonial sites, as well as the first settlements of later immigrants of the Mexican and Texas Republics.

One of the most important sites along the Camino Real in East Texas is located near the east bank of the Neches River along State Highway 21. Unlike some of the obscure landmarks along the trail, this site can be visited easily. Known as El Cerrito (the little hill) in the 19th century, it is today the Caddoan Mounds State Historical Park. A route of the Camino Real and its ford across the nearby Neches River, almost certainly following an ancient Indian trail, were located just north of the mounds. Its presence illustrates the blending and convergence of prehistoric, American Indian, European and Texan cultures on a single point of the historic landscape.

From the Angelina River eastward, the Camino Real passed in the vicinity of the early Spanish colonial mission site of Nuestra Señora de la Purísima Concepción de los Hainais and the nearby presidio Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de los Tejas. The mission was withdrawn and eventually relocated to San Antonio in 1731. Closer to the community of Nacogdoches, the trail crossed Bayou Loco near a small Caddo Indian village dating to about 1715. In 1976, archaeologists from the University of Texas found that the site also contained French artifacts.

Nearby, the modern city of Nacogdoches contains the remains of another early Spanish mission, Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Pilar de Nacogdoches. Beyond Nacogdoches, archaeologists from Stephen F. Austin State University relocated the early mission site of Nuestra Señora de los Dolores de los Ais that was first established by Domingo Ramón in 1717 and re-established by the Aguayo expedition of 1721-22. Excavations since 1977 have found interior and exterior walls and thousands of artifacts.

The changing trails of the Camino Real continued toward and across the Sabine and can often be traced on local historical land grant maps. The terminus of the trail is the remains of the Spanish presidio of Nuestra Señora del Pilar de los Adaes near today’s Robeline, Louisiana.

The Future of the Camino Real

The Camino Real has often been the focus of both popular and historical interest throughout the 20th century. Recently, the National Park Service proposed that it be designated a National Historic Trail and, ironically, has encountered private property-rights issues, possibly by some of the descendants of settlers associated with the historic trail.

Regardless of its political future, the significance of the Camino Real is so clearly embedded in both the history and development of the region that its importance will be recognized for generations to come.

— written by Al McGraw for the Texas Almanac 2002–2003. Mr. McGraw is an archaeologist for the Texas Department of Transportation in Austin and has worked in Texas archaeology for more than two decades at prehistoric and historical sites from the Rio Grande to East Texas. He is the author of numerous archaeological publications.

SOURCES

Journey to Mexico During the Years 1826 to 1834 by Jean Louis Berlandier; Trans. by Sheila M. Ohlendorf, Josette M. Bigelow and Mary Standifer; Texas State Historical Association in cooperation with the Center for Studies in Texas History, University of Texas, Austin, 1980.

Our Catholic Heritage in Texas, 1519-1936: Volumes 1-4 by Carlos E. Castañeda; Von Boeckmann-Jones Co., Austin, 1936.

San Juan Bautista: The Gateway to Spanish Texas by Robert S. Weddle; University of Texas Press, Austin, 1968.

Spanish Texas, 1519-1821 by Donald E. Chipman; University of Texas Press, Austin, 1992.