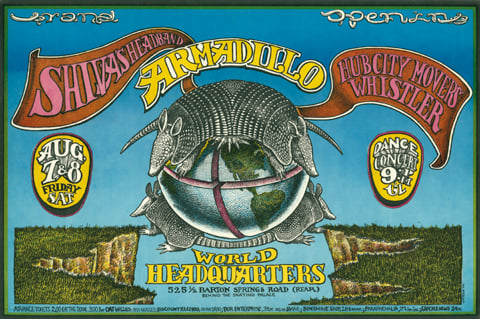

Over the summer of 1970, a loose collective of hippies, free spirits, and dreamers refashioned the old National Guard armory building at the corner of South First Street and Barton Springs, just across the Colorado River from downtown Austin, into a concert hall and beer garden.

The Armadillo World Headquarters was all about music, a shared tolerance for marijuana, psychedelic drugs, and cold beer, and like its namesake had a hard-shell interior with a docile disposition. During its first two years of operation, the Armadillo brought in a parade of touring talent who otherwise would have bypassed Texas, including Ry Cooder, Captain Beefheart, Taj Mahal, Dr. John the Night Tripper, Frank Zappa, the Flying Burrito Brothers, the New Riders of the Purple Sage, Bill Monroe, and especially Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen.

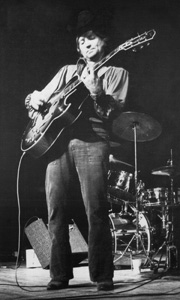

But it wasn’t until the night of Aug. 12, 1972, when Willie Nelson walked onto the stage of the Armadillo that everything changed. That performance in front of a mixed crowd of hippies and rednecks is recognized as the starting point of the modern Austin music scene.

A vibrant music community was already in the making, articulated by several outsiders who relocated to Austin like Nelson did to make music unfettered by commercial restraints. Most prominent were Jerry Jeff Walker, a New York folkie from the Greenwich Village scene who had written a hit song about a New Orleans street dancer called “Mr. Bojangles,” another singer-songwriter from Houston named Guy Clark, whose vivid story songs had been covered by Walker, and a lanky Fort Worth kid with high cheekbones and a taste for liquor named Townes Van Zandt, considered by his peers as the purist songwriter of all.

Walker also fronted the Lost Gonzo Band. Their live recording Viva Terlingua! — made in 1973 in the old Hill Country dancehall at Luckenbach (pop. 3) withfiddler Sweet Mary Egan and a harmonica player named Mickey Raphael — set thestandard for rowdy Texas-style country rock. It was the first“made-in-Austin” album to go gold.

The Lost Gonzos — Gary P. Nunn, Bob Livingston, Michael McGeary, Herb Steiner, Craig Hillis, and Kelly Dunn — performed as the Cosmic Cowboy Orchestra whenever they supported Micheal Murphey, the flaxen-haired, buckskin-loving singer-songwriter from Dallas with the two best-selling albums in Austin, Geronimo’s Cadillac and Cosmic Cowboy Souvenir. Murphey came out of the same Rubiyat Club folk scene in Dallas where a husky-voiced belter named B.W. Stevenson from Murphey’s high school, Adamson, developed his robust singing style that led to several hit singles, notably “My Maria,” No. 9 on Billboard’s pop singles chart and No. 1 on the adult contemporary chart in 1973.

Another Adamson grad and Rubiyat regular, Ray Wylie Hubbard, was beginning to make forays down to Austin from Red River, New Mexico, where he had a music club, while another Rubiyat vet, Willis Alan Ramsey, recorded his debut album for Leon Russell’s Shelter Records showcasing a country/folk/rock songcraft so exquisite he would never make another album.

Jerry Jeff Walker frequently worked as a solo act at Castle Creek, a listening room a block from the State Capitol that showcased singer-songwriters. Walker arranged for a friend of his from Florida named Jimmy Buffett to sit in between sets before getting his own gig. Castle Creek inspired a song Buffett was crafting called “Wasting Away In Margaritaville” that would become his calling card.

A San Antonio native named Doug Sahm came to Austin from the other direction, relocating from San Francisco where his rock ’n’ roll Tex-Mex flavored band, the Sir Douglas Quintet, had gone after their 1966 pop hit “She’s About a Mover.” A homesick Sahm chose Austin over San Antonio for its tolerance of people who looked and acted different. Besides, he had been playing the city since he was a seven-year-old lap steel guitar prodigy who sang country.

Music-making had historically been a provincial and low-key affair in Austin. Scholz’ Garten, established by August Scholz in 1866 and still the home of the Saengerrunde German singing club, was the city’s oldest drinking establishment.

The abiding appreciation of folk music and traditional music could be traced to 1909 when University of Texas assistant extension school director John Lomax and professor Leonidas Payne co-founded the Texas Folklore Society. Within six months, there were 92 charter members.

Fifty-five years later, Kenneth Threadgill’s filling station and beer joint on North Lamar served as the informal meeting place for folk music aficionados, including a young University of Texas student named Janis Joplin who showed up to sing and play at the weekly hootenannies. When properly inspired and lubricated, Mr. Threadgill would cut loose with yodels in the style of Jimmie Rodgers, country music’s first star.

Before Willie, traditional country music had been largely limited to a few bars and dancehalls such as Big G’s, Dessau Hall, Big Gil’s, and the Broken Spoke, and bands such as Dolores and the Bluebonnet Boys, the Moods of Country Music, Johnny Lyons and Janet Lynn & the Country Nu-Notes, Jess DeMaine and the Country Music Revue featuring Mary Margaret Kyle, and Bert Rivera and the Night Riders, whose leader had several years road experience as Hank Thompson’s steel guitar player.

In 1970, Freda & the Firedogs, a band of like-minded college students led by a dark-haired Cajun pianist named Marcia Ball, aka Freda, tapped into the traditional country zeitgeist and started drawing an unusually strange mix of students, bikers, Mexican families, hippies, hillbillies, and old-time country music fans to the Split Rail Drive-Inn on South Lamar.

Similarly, a small clutch of white kids were drawn to East Austin to soak up the African-American sounds of performers such as Erbie Bowser, Blues Boy Hubbard, T.D. Bell, Hosea Hargrove, and barrelhouse pianist Robert Shaw at clubs including the Victory Lounge, the IL, Charlie’s Playhouse, Ernie’s Chicken Shack, and Marie’s Tea Room Number 2. The white blues kids had their own playhouse, the One Knite on Red River Street, a half block from the police station where the Storm, featuring Dallas’ Jimmie Vaughan on guitar and Lubbock’s Lewis Cowdrey on harmonica, and the Nightcrawlers, the band headed by Irving drummer Doyle Bramhall and including Jimmie Vaughan’s little brother Stevie, were part of the weekly lineup.

Mexican-Americans had their own music scenes in clubs along East Sixth Street and in salons de baile on the edge of town where conjunto combos fronted by Johnny Degollado (El Montopolis Kid) and accordion maestro Camilo Cantu and Tejano big bands such as Ruben Ramos, aka El Gato Negro, and the Mexican Revolution played for dancers.

Rock ’n’ roll bands played cover versions of popular songs at fraternity and sorority parties at The University of Texas, but by the mid-1960s, some bands began to dabble in original music, most significantly the 13th Floor Elevators, a pioneering psychedelic band led by a yowling Travis High School dropout named Roky Erickson that had a national Top 40 hit in 1966 called “You’re Gonna Miss Me” distinguished by an electric jug. The Elevators and like-minded rock bands worked in such places as the Old New Orleans around the UT campus.

By the late 1960s, Austin had its first hippie venue, the Vulcan Gas Company at 300 Congress Avenue, inspired by music ballrooms in San Francisco where many Austin musicians and hangers-on had migrated. The Vulcan was the predecessor to the Armadillo, featuring local and touring psychedelic rock, folk, and blues artists and led to the discovery of an albino blues guitarist from Beaumont named Johnny Winter, who opened for blues giant Muddy Waters. House bands included Shiva’s Headband and the Conqueroo, an eclectic folk-rock-blues-jazz group. Vulcan shows were promoted with posters created by Gilbert Shelton, the creator of the Furry Freak Brothers, and other underground artists, and Jim Franklin, who made the armadillo into the iconic symbol of Texas hippies.

Willie Nelson became Austin’s music catalyst through his Nashville connections and extensive body of recorded work, and because he represented the kind of country music the rock ’n’ rollers and the folkies were trying to project in their own sounds. At 39, he was older than the student-aged musicians and had experience with publishing and recording contracts. And while he came to town clean-shaven with his hair barely covering the tops of his ears, he adapted quickly, letting his hair grow long, cultivating a beard, dressing on stage in blue jeans, tennis shoes, and T-shirts, with a bandanna around his neck or head, and an earring in his lobe.

With bass player Bee Spears wearing a headband and moccasins in Indian fashion and drummer Paul English performing with a black cape with red lining draped over his shoulders, and new addition Mickey Raphael, an Afro-haired harmonica player who had been playing with B.W. Stevenson, Willie Nelson and band fit right in in Austin.

Nelson’s groundbreaking Armadillo performance in 1972 opened with a string of early songwriting hits — “Crazy,” “Hello Walls,” “Funny How Time Slips Away,” and “Nightlife” — to introduce himself to those in the audience who had never heard him before, then demonstrated his guitar-playing prowess as his band alternated sets with young country-rockers Greezy Wheels until closing time at midnight. Afterward, the show moved to a suite at the Crest Hotel across Town Lake that writers Edwin “Bud” Shrake and Gary “Jap” Cartwright had rented, where a guitar pulling ensued featuring Willie Nelson, with University of Texas football coach Darrell K Royal calling out requests and making sure the audience adhered to his rule to respect musicians and the music they were making: “If I can hear you, then you are too loud. If you wish to socialize, please go out on to the front or back porch.” Those who failed to observe the rule were asked to leave.

Willie Nelson’s first show at the Armadillo coincided with the appearance of KOKE-FM, an Austin radio station that coined the phrase “progressive country” to explain its eclectic playlist, which included Ernest Tubb and classic Texas honky-tonk, Bob Wills and the Made-in-Texas sound called western swing, Nashville rebel Waylon Jennings, as well as the Byrds, the Rolling Stones, Creedence Clearwater Revival, and lots of Willie Nelson, who also sang jingles for the station and played impromptu shows on the air with friends such as Kris Kristofferson. Progressive country would also be labeled as redneck rock, Texas music, and outlaw country. Whatever it was, the music sounded like nowhere else but Austin.

In 1974, Willie added television to his Austin portfolio when he agreed to perform in front of cameras at Studio 6A on the campus of The University of Texas at Austin for KLRN-TV (now KRLU-TV), the Public Broadcasting Service television channel serving San Antonio and Austin. KLRN program director Bill Arhos, producer Paul Bosner, and director Bruce Scafe secured grant money to film a pilot for a live music series focusing on original Texas music. The pilot led to the first broadcast of Austin City Limits in 1976. The series is the longest running music program on American television.

Willie would proceed to further invest in the Austin music scene by buying the old Terrace Motor Inn on Academy Street, just off South Congress Avenue, and by helping transform the Terrace’s convention center into the Texas Opera House, later known as the Austin Opry House, where he built a recording studio, before moving his operations to near Spicewood in the Hill Country west of the city where his empire included the most modern recording facility in Texas, a golf course, a western town, and condominiums.

— Joe Nick Patoski has been writing about Texas and Texans for four decades. His biography Willie Nelson: An Epic Life was published by Little, Brown & Company in 2008 and was recognized with the 2009 TCU Texas Book Award for the best book written about Texas. The article was written for the Texas Almanac 2012–2013.